Learn more about Dr. Goodwin’s amazing class here and follow the hashtag #SyrRelBodies on Twitter for a well-curated discussion of US religions and the regulation of bodies of color.

1. Tell us about #SyrRelBodies. Describe the project.

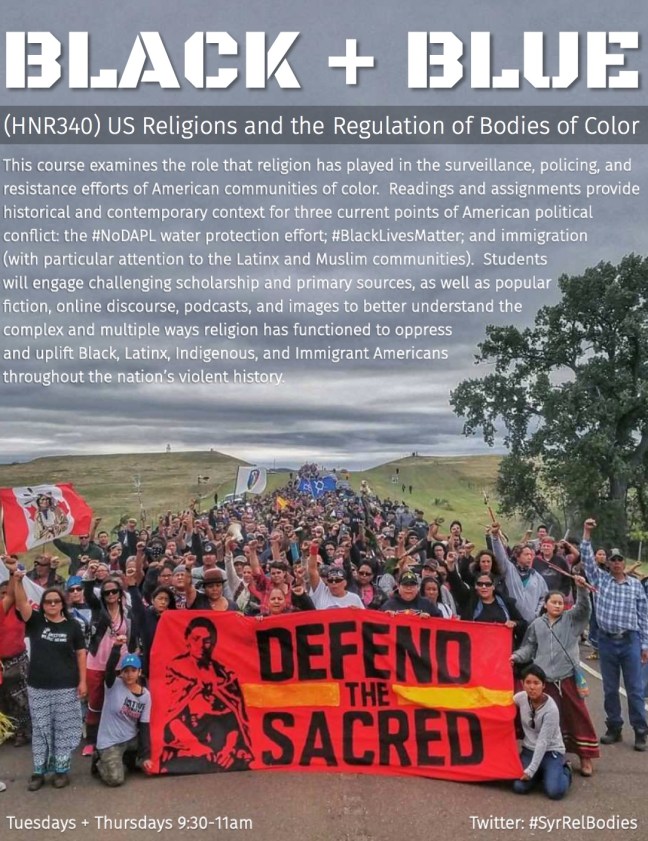

#SyrRelBodies is the hashtag for “Black+Blue,” my honors course on American religion and the regulation of bodies of color. The course is divided into three units that focus on contemporary activist movements: #NoDAPL and indigenous religion(s); #BlackLivesMatter and African American religion(s); and immigration, which includes both Islam and Latinx religion(s).

Before the start of class, I used the hashtag to catalogue stories and sources I wanted to consider for inclusion on the syllabus. At the beginning of term, I used the hashtag to share news stories and articles of interest with class members. The students also use the hashtag to share pertinent links, to live-tweet Duvernay’s The 13th, which we watched in class as part of the Black Lives Matter unit, and as a way of building community and boosting their participation grade outside the classroom.

.@ProfIRMF TFW @ProfIRMF references Johnson’s definition of racialization and it is the perfect segue b/w #SyrRelBodies units pic.twitter.com/GUgUncXFtT

— Megan Goodwin (@mpgPhD) April 5, 2017

2. Who or What sources informed the project?

This was a class born from Twitter: two of our three units directly address political resistance articulated and organized through hashtags. This is also the first upper-division class I’ve taught in almost five years, and the reading load is pretty heavy, even for honors students. So I’ve augmented reading assignments, particularly the dense historical ones, with links to smart blog posts (like Judith Weisenfeld’s great piece about religion at the NMAAHC) and short podcasts (including Gene Demby’s reflection on visiting Elmina Castle) to demonstrate the connections between the case studies and contemporary struggles.

The course’s single biggest influence beyond Twitter was Sylvester Johnson’s phenomenal African American Religions, 1500-2000. His argument about the imbrication of democracy, freedom, colonialism, and imperialism (or, to use his shorthand, “freedom and its others”) forms the core of our learning objectives.

3. What did you intend for your students to learn?

At this point all of my classes get hashtags. I started doing this for my “Religion and Monsters” class at Bates – we watched a number of films, and I wanted the students to apply the day’s keyword to each film in real time. They Storified their tweets as part of their final project. Any time we watch films in my class, we’re live-tweeting them in response to discussion questions: this helps direct students’ viewing and motivates them to stay engaged with the material rather than to just zone out. Social media also provide alternative modes of participation for students who are reticent to talk in class as well.

#SyrRelBodies is a lot more like what I’ve done with my religion and politics classes at Bates and Syracuse, though: my politics classes use Twitter because Twitter has become a primary method of news and political communication, and its vital that the students cultivate social media literacy as part of their education in American politics.

With this in mind, one of the primary goals for #SyrRelBodies was cultivating media literacy, beginning with how to identify a credible news source and moving through building a network of informal credible sources within political movements. I explained, for example, that often mainstream news sources lag significantly behind Twitter, and sometimes fail to cover major protest efforts at all. At the same time, there’s a lot of noise on Twitter. So we talked about identifying credible sources within the movements. (For example, I follow Ruth Hopkins, who is a Native journalist affiliated with Indian Country Today for news on #NoDAPL and other indigenous activism.)

4. What did you observe them learning?

Some are more excited about using Twitter than others, but the students who like it curate an ongoing conversation about race, religion, and American politics that continues outside the classroom and perhaps beyond the semester. When they live-tweeted The 13th, I could see them putting the film into conversation with course readings and class discussions. I also found that they were staying up to date with current news and becoming more comfortable identifying credible sources.

5. What did you learn about your own pedagogy in carrying out the project?

Mostly that I love Twitter and will continue to use it in future classes, at least until I can figure out how to make Snapchat pedagogically effective.

6. What advice would you offer to anyone wanting to do this project in their own class?

Two things: one procedural, one ethical. First, if you’re planning to use a class hashtag and your students aren’t already on Twitter, it’s important to have them fill out their bios and upload a user picture. The picture and bio don’t have to identify them in any way, but it’ll help the Twitter search engine recognize them as legitimate users. They should also tweet for a while without using the hashtag. If you’re a new account without a bio or a user photo, and/or you only tweet on one hashtag, your tweets won’t show up on the hashtag search. (Which will lead to students insisting that they’ve done the assignment while you search fruitlessly for their tweets.)

Second and more importantly, the internet is not a safe space for women and people of color. Part of cultivating social media literacy is teaching students to be good internet citizens (or, as we like to say, not to be jerks on the internet), but also to protect themselves from abusive users. I don’t require students to use their real names or pictures in their Twitter accounts, and I encourage them to block and report abuse with a swiftness.

Megan Goodwin, PhD is Visiting Assistant Professor of Religion, Race, and Politics at Syracuse University. Her research focuses on the ways gender and sexuality influence mainstream American interactions with contemporary minority religions. Follow her on Twitter @mpgPhD.

Megan Goodwin, PhD is Visiting Assistant Professor of Religion, Race, and Politics at Syracuse University. Her research focuses on the ways gender and sexuality influence mainstream American interactions with contemporary minority religions. Follow her on Twitter @mpgPhD.