In “Comparing the Games We Play: The Limits of Privilege-Checking,” Richard Newton questioned the tactics of policing privilege. Amanda Robbins responded with a discussion on the effects of this discourse, musing on ways to constructively discuss privilege. In this third post, Samantha Poremba considers the social ramifications of identifying privilege.

—

“Checking privilege,” a hip hashtag and millennial social movement, has an interesting connotation. When I think of the word “checking,” I envision crossing an item off a to-do list without much thought. In many ways, checking privilege is just that—a quick examination without deeper reflection.

Arguably, the spirit behind the “checking privilege” movement is one of good intent in that it is designed to raise awareness on various hierarchies and collisions of our own identities. However, when we only stop to check our privilege and do not take the time to deeply evaluate or reflect on our place within greater systems, we might be, as Richard Newton argued in his previous post, making matters worse.

When we tell an individual to “check your privilege,” we are in fact, putting ourselves in a position of power. It is as if our knowledge of their perceived privilege removes us from having any role within this system—enabling us to judge them.

Privilege and Social Systems

Dr. Beverly Tatum approaches social systems as a blend of micro-level and macro-level elements. They involve cultural messages, institutional policies and practices, as well as the beliefs and actions of individuals[1].

-

18th century scold’s bridle in the Märkisches Museum Berlin, Photo taken by Angoria. Used under CC BY 3.0

Furthermore, I would argue Max Weber’s theory of the iron cage of rationalization would apply to this concept in that over time, society has further rationalized and tightened control over such systems.[2]

As a result, a system typically designed to privilege a group empowers that group, enabling it to protect itself. This defensiveness, Tatum argues, has become an increasingly rationalized and ingrained feature of our society.

Looking in All the Wrong Places

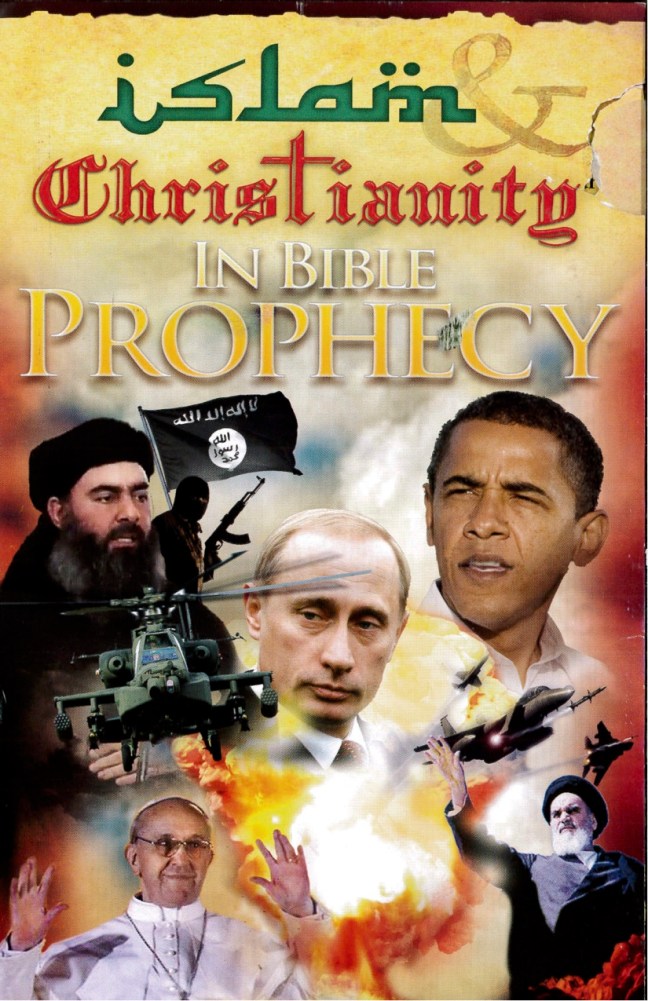

The other day in my Islam class, I was chatting with classmates and we were outraged that the religious pamphlet above had been mailed to a peer’s home. Dr. Newton used our conversation as a teaching moment to state that often, the most hateful and dangerous aspects of our society go unseen. Examples like this could call us to examine our own privilege in relation to the abhorrent aspects of a larger system.

For example, rather than simply calling out the author as a hateful, misinformed individual, I could have asked myself how and why I perceive this one, white, male, U.S. citizen as using religion as a basis to perpetuate hate about America’s Muslim minority. What else is there to acknowledge?

We are quick to analyze issues at the surface and assign blame to those perpetuating disdainful acts. But what of the larger issues within our society that could be affecting or even causing these hateful moments? Should we stop looking at macro-level systems and the implications associated with them when we examine issues surrounding hate, bias, and prejudice?

What is perhaps even more dangerous in a situation such as what occurred the other day, is rationalizing these horrendous politics. I would argue that there are people who received the very same pamphlet in their mailbox and internalized the message being sent within the materials. As a “reputable” source (due to the presenter’s identity), readers might come to interpret the scenes referenced as reason to terrorize the entire Islamic community.

Beyond Checking Privilege

Privilege and its effects have become so ingrained in our system that we do not fully see how they play out within our culture, institutions, and individual philosophies and actions. Therefore, when we “check privilege” we are acknowledging what we can see and what Weber would argue is the structure itself.

Yet we are looking at only an extremely micro-level tier that contributes to a greater dynamic. In so doing, we disregard the effects of other intersecting identities, the history and context of the system, and the individual interactions that result in its construction.

In order to truly affect the system, we have to examine privilege to understand the unseen inner workings of bureaucratic schemes. In order to effectively undo the rationalization of many “isms” at various points of the system, it requires a deeper reflection on our own roles within this organization. Furthermore, it demands that we look at all that could be affecting a disdainful act and looking beyond what we see at the surface in moments such as I discussed earlier.

So perhaps it is time to start changing our language from “check your privilege” to something more along the lines of “beyond the surface.”

[1] Beverly Tatum, Why are all the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? (New York, New York, Basic Books, 1997).

[2] Max Weber. Political Writings, ed. Peter Lassman, trans. Ronald Speirs (Cambridge, United Kingdom, Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought, 1994).

Samantha H. Poremba ‘16 is a senior at Elizabethtown College. She is a Sociology-Anthropology major with minors in both Women & Gender Studies and Peace & Conflict Studies. Samantha is currently collaborating with TeachUNICEF for her Honors in the Discipline (HID) thesis.

One thought on “Privilege Beyond the Surface”